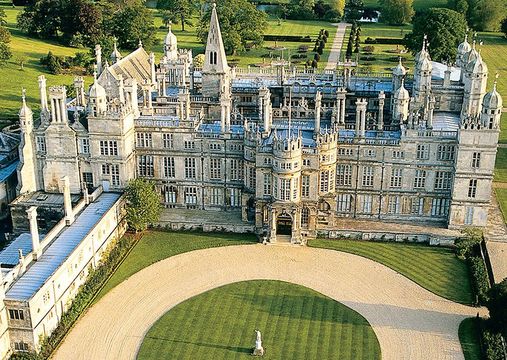

Grandest and largest house of the first Elizabethan Age, Burghley House has remained in the Cecil family since Lord Burghley was ennobled in 1571.

The jewel of the first Elizabethan Age, in Peterborough, Stamford, twinkles still.

A among the many treasures to be discovered along the old Great North Road between London and Edinburgh is majestic Burghley House in the southern Lincolnshire market town of Stamford.

The largest and grandest house of the Elizabethan Age, Burghley was built by William Cecil, principal secretary and lord treasurer to Queen Elizabeth I. Generally regarded as the Tudor Queen’s most respected councilor, Cecil was well into the building of the house when Elizabeth ennobled him as Lord Burghley in 1571. Cecil’s son was created Earl of Exeter, and the house and title have stayed in the family ever since.

It took 32 years to complete Burghley House. Today the palatial building stands looking much as it did at the end of the 16th century. The stately home’s interior, however, took its present appearance a century later. John, the 5th Earl, and his wife, Lady Anne Cavendish, were among the first of the Grand Tour-ists. On four trips to France and Italy, they acquired more than 300 important paintings and commissioned tapestries, statuary and furniture. In his refurbishment of the family seat, the earl brought in the finest craftsmen of his day, including woodcarver Grinling Gibbons. It was eminent Italian painter Antonio Verrio, though, who really livened the place up.

Read more

The famous artist came to Burghley after years of royal painting at Windsor, and spent more than a decade creating the home’s lavish ceilings. Scenes from Greek and Roman mythology predominate in lush colors in the State Rooms known as the four George Rooms and the Hell Staircase. It is the Heaven Room, however, that is considered the finest example of Verrio’s work anywhere. The gods and goddesses of mythology took Verrio 75 weeks to complete.

Though Burghley House continues to be home to the Cecil family, the house and its treasure-trove contents are part of a charitable trust established in 1981. Today, the house and gardens, some 1,300 acres of parkland and an estate of 13,000 acres are administered by the Burghley House Preservation Trust.

Jo Tinker, the assistant house manager, showed me around this spring just days before Burghley flung wide its doors to the public for the season. The sense of anticipation was everywhere. A circuit of the 18 first-floor rooms that are open to view covers more than a quarter of a mile. Having visited scores of noble residences from St. Michael’s Mount to the Grampians over the years (and written about many of them), I would rank Burghley high in the premier division of great “Great House” visits.

More than 1,000 paintings and 400 drawings adorn the reception rooms and state bedrooms. The Old Kitchen on the ground floor was used well into the 20th century. “After 1920, they realized how cold and impractical it was,” Tinker said.

There are 115 rooms in all under Burghley’s three-quarters-of-an-acre roof and untold corridors and bathrooms, cupboards and service areas.

Given the immense size of Burghley, the Great Hall is almost disappointingly not great. Tinker explains: “By the time that the house was finally finished, halls were already going out of fashion. So, there has always been a hall here, but it was never used very much.”

Still, every Christmas, the Great Hall is the scene of the staff Christmas party, where as many as 300 estate workers and friends gather for festive cheer.

If Burghley House itself is Elizabethan, its surrounding gardens and parkland are decidedly 18th century. It was the 9th Earl who brought in the legendary Lancelot “Capability” Brown to bring the landscaping up to modern 18th-century style. “Nature improved upon” was the theme of the day.

The Old Kitchen is one of the few parts of the house where Burghley’s Tudor origins are visible.

In his usual fashion, Brown took away some small hills, built others, constructed a lake and generally altered the land beyond recognition. A deep haw-haw around the expansive lawns gave Burghley’s occupants an unobstructed view of the pastoral vistas Brown created. It may not be exactly natural, but it would be a hard view to improve upon today.

More recently, a 12-acre scrub woodland has been reclaimed and transformed into the Sculpture Garden. Mown paths and a lakeside walk lead through an impressive collection of contemporary sculptures enriched by pieces displayed in an annual exhibition.

COURTESY OF THE BURGHLEY HOUSE

Over the generations, of course, succeeding Cecils each put their own stamp on Burghley and played the roles in Parliament and Privy Counsel befitting their lofty station. The 10th Earl was elevated to the rank of Marquess in 1801.

Perhaps the most celebrated of his descendants has been the 6th Marquess of Exeter. David, Lord Burghley, was Britain’s premier hurdler from 1924-33, winning Olympic gold in the 400-meter hurdles at Amsterdam in 1928 and silver in Los Angeles four years later. A somewhat fictionalized Lord Burghley was the basis for Lord Lindsay in the film Chariots of Fire. Lord Burghley went on to head the British Amateur Athletic Association and stage the 1948 London Olympics. In 1961 he inaugurated the famous annual Burghley Horse Trials.

Master Italian painter Antonio Verrio’s ceiling in the Third George Room portrays the reunion of Cupid and Psyche surrounded by their attendants and lesser deities (Courtesy of the Burghley House).

Despite welcoming tens of thousands of visitors every year, Burghley House is hardly content to rest on its historic laurels. This year sees the opening of Burghley’s unique Gardens of Surprise. Mixing classic and modern design, the new Tudor-inspired garden is dedicated to Cecil, who was himself a passionate gardener and garden designer.

It’s a bit of a stretch. The boxed hedges, geometrical plantings and trim pebbled walkways would be familiar to the first Lord Burghley. It is less sure what the 16th-century statesman might make of the inevitable soaking from the garden’s 30 water features, a mirror maze and revolving Caesar’s bust. But Tudor or not, from its huge Elizabethan-style sundial to the gemstone-studded grotto, the Gardens of Surprise is great fun and family entertainment.

The gardens and parkland of Burghley draw visitors to the estate throughout the year. New in 2007, Burghley’s Tudor-inspired Gardens of Surprise features a finely calibrated sundial, grottos and water hazards galore.

Burghley House does indeed welcome visitors, from the end of March until late October every year, every day except Fridays. ’Tis a worthy highlight indeed to any visit into the East Midlands, or perhaps while you are pottering along the Great North Road.

* Originally published in 2016.

Comments