This innocent Fife farmhouse hid the entrance to Scotland's underground bunker.

Aspiring travel writers are invariably advised to avoid the clichéd opening: “This well-kept secret” but, in this particular instance, it is 100 percent appropriate.

Scotland’s Secret Bunker was built at the start of the Cold War in 1951 underneath an innocent-looking “farmhouse” near St. Andrews, Fife, as part of the British response to the Cold War. Now a tourist attraction, the Bunker gives a unique opportunity to understand what life would have been like during and after a nuclear attack.

Sitting on a base of gravel meant to absorb the shock waves of a nuclear explosion, the Bunker is some 135 feet underground, protected by an outer shell of 10-feet-thick concrete, reinforced every six inches with one-inch-thick tungsten rods. For increased protection, the structure is lined with brick, covered with netting and soaked with pitch to provide a secure shell. The excavated earth laid over the structure with concrete rafts at intervals acts as another barrier. In all, it is estimated that some 45,000 tons of concrete was used in the Bunker’s construction.

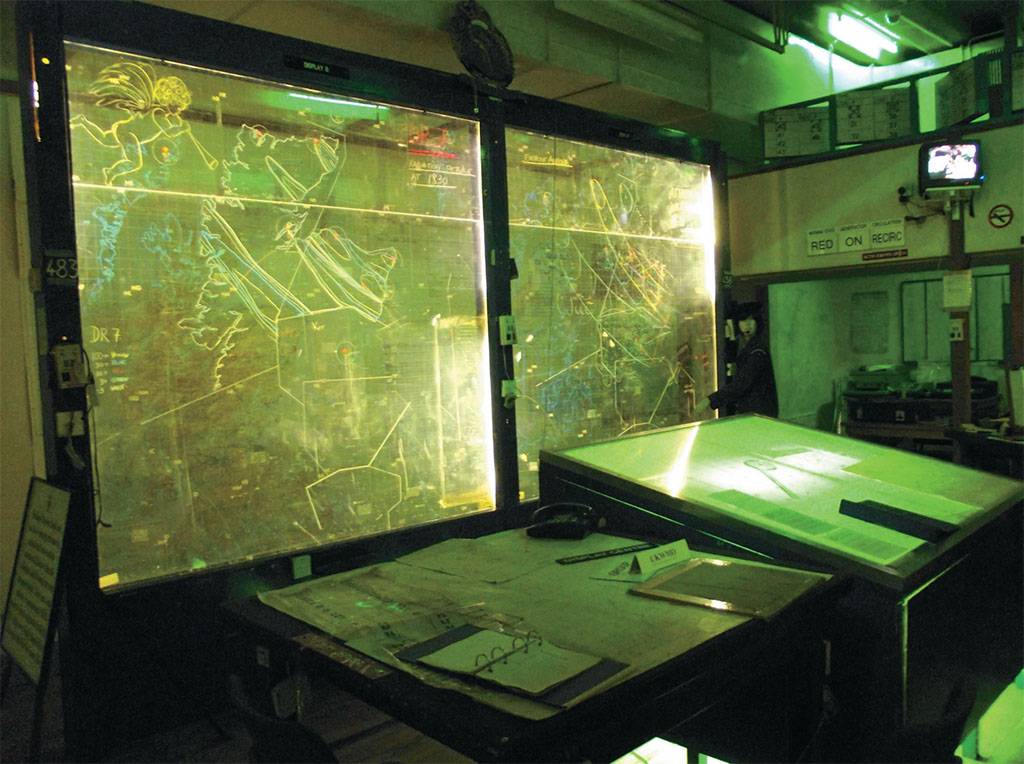

In the control center, Royal Observer Corps operators plotted bomb bursts and monitored fallout. FORBES INGLIS

The “farmhouse,” which is built of concrete and steel, doubled as the guardhouse and the entrance. Initially, it provided accommodation and administration space, but later housed food stores, with the roof space being utilized as a storage tank containing 2,400 gallons of water.

Read more

Although the Bunker would not have survived a direct hit, it was designed to withstand the effects of a bomb landing as close as three miles away. The Bunker had a number of military functions, before the intensification of the Cold War made nuclear war more likely and the site became a Regional Government Headquarters in 1968. Prior to any attack, Government ministers and senior civil servants would have moved to the relative safety of the Bunker and run Scotland from there.

FORBES INGLIS

As you walk down the sloping tunnel, you slowly realize you are leaving the outside world behind. The tunnel is 150 yards long, encased on both sides with concrete, 18 inches thick at the surface increasing to 10 feet thick beside the two large blast doors, each of which weighs 1.7 tons. Just before the doors, the tunnel bends, a device designed to mitigate the effects of any blast and to make the Bunker easier to defend, whether from enemy forces or contaminated locals.

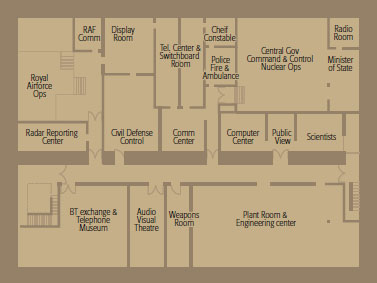

The Bunker’s hub of operations is the Nuclear Command Control Center, securely located on the lower level. There, officials from government departments such as transport, trade, agriculture, fisheries and social security, along with senior fire and police officers, scientific and meteorological staff would have analyzed the reports available to them and so predicted patterns of radioactive fallout, and generally monitored the results of any nuclear strike.

FORBES INGLIS

The Minister of State, the man in overall control of the Bunker, had an office overlooking the Control Center. From there, or the attached viewing gallery, he would have assessed the latest information, much of it displayed on giant maps. Following discussions with senior officials, he would have issued instructions or advice to the survivors on the surface.

Life goes underground

The Secret Bunker – “Scotland’s best-kept secret” – is open from 10 a.m. between mid-March and October 31. www.secretbunker.co.uk

Travel north from Edinburgh across the Forth Road Bridge. From junction 2A take A92 and follow signs to Kirkcaldy, then follow the coast road A955 (Methil) and then A917 (Anstruther). From Anstruther, take the B9131 and then follow the signs for the Secret Bunker. The total journey time is approximately 90 minutes.

On the back wall are red and black telephones to issue final warnings to any attacker. If all else failed, a series of numbers known as “the nuclear command key” repeated on the telephone would have set a retaliatory strike in motion.

Any decisions needed to be communicated to the personnel staffing some 14,000 locations around the country—police and fire stations, government offices—that would then be responsible for passing the information on to the 70 percent of the British population it was estimated might survive. Maintaining communications with other government centers and with survivors would therefore have been a key function.

The Bunker had an extensive telephone and teleprinter system, with 500 internal lines and 2,800 external lines, manned 24 hours a day by 10 staff. In order to maintain telephone communications, the whole Bunker is encased in “Faraday cage,” a device to protect the telephone system from the electromagnetic pulse that follows a nuclear bomb blast.

The other element of the communications system was the BBC’s broadcasting studios. Following any nuclear attack, all radio and television services would have ceased broadcasting, even if they had the capability of doing so.

The Bunker hosted a radio engineering workshop, studio edit suite and a soundproof room, all geared to allow the technicians and press officers who formed the Wartime Broadcasting service to produce emergency broadcasts to the general public on topics such as up-to-date war news, official announcements, survival advice and nuclear fallout forecasts.

Conditions inside the Bunker are strictly controlled. The air intake system can filter out radioactive particles and protect against attack by gas or biological means. The ventilation system can also refrigerate, ozonate, de-ozonate, humidify and de-humidify the air.

Life inside the Bunker would have been extremely basic, but attractive given the alternative. The top people in the Bunker had their own bedrooms, (the Minister of State had a bed in his office), while those lower down the scale had to share with one or two others. For most of the staff, however, there was a “hot bed” system. Six dormitories provided sleeping accommodation for 300 people expected to work for 18 hours and sleep for the remaining six, who would have slept in shifts.With no natural light, there was no need for day and night shifts.

It is likely that the Armory, with its heavy-duty doors, would have contained top-secret papers as well as weapons, and possibly a stock of cyanide for workers to take should the main and emergency tunnels collapse or long-term radioactivity render life outside impossible.

Although used regularly for exercises, the Bunker was thankfully never required to fulfill its nuclear war role.With international relations having changed radically, the British government cancelled plans for an expensive face lift in 1992, and sold the building to its present owners to be run as a heritage center. Although the site was officially removed from the secret list the following year, a number of areas still remain off-limits to the public and, in theory at least, the Bunker could be brought back into use should the international situation deteriorate.

Comments