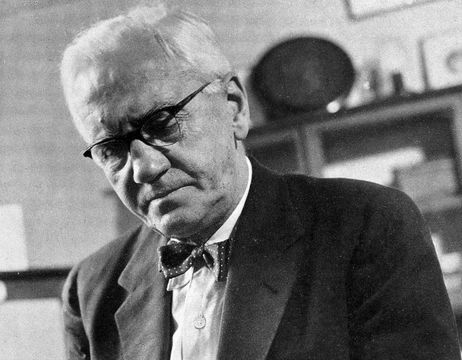

Sir Alexander FlemingCreative Commons / Wellcome

Sir Alexander Fleming's accidental discovery of penicillin changed the course of medical history, propelling humanity into the antibiotic era. Born August 6, 1881, his relentless pursuit of scientific knowledge and determination to improve human health set an example for generations to come.

In the annals of medical history, certain individuals stand out as pioneers who revolutionized the course of human health. One such visionary was Sir Alexander Fleming, a Scottish biologist and pharmacologist, whose accidental discovery of penicillin in 1928 marked a monumental turning point in the fight against bacterial infections. His groundbreaking work laid the foundation for the antibiotic revolution and saved countless lives. This article delves into the life, achievements, and lasting legacy of the man behind the microbial miracle, Sir Alexander Fleming.

Alexander Fleming was born on August 6, 1881, in Lochfield, Ayrshire, Scotland. His upbringing in a rural environment instilled in him a deep appreciation for nature and the world around him. His early education took place in local schools, where he exhibited an insatiable curiosity about the natural sciences.

In 1895, Fleming's father passed away, leaving his family with limited financial means. Despite the challenges, young Alexander persevered, demonstrating academic excellence that earned him a scholarship to attend the prestigious Kilmarnock Academy. In 1901, he enrolled at St. Mary's Hospital Medical School in London, commencing a journey that would forever change the course of medicine.

After graduating with distinction in 1906, Fleming began his career as a bacteriologist under the mentorship of Sir Almroth Wright. His early work focused on studying bacterial infections and developing immunization methods against typhoid fever. During World War I, Fleming served as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, where he gained invaluable experience in treating wounded soldiers and witnessed the devastating effects of infections.

It was in 1928, while working at St. Mary's Hospital, that Fleming stumbled upon the serendipitous moment that changed the world of medicine forever. A petri dish containing Staphylococcus bacteria had been accidentally contaminated with mold spores. To his astonishment, Fleming noticed that the bacteria around the mold had died, creating a clear zone of inhibition.

He identified the mold as Penicillium notatum and aptly named the substance it produced "penicillin." Realizing the potential of this accidental finding, Fleming set out on a mission to study penicillin's properties further and its potential in combating infectious diseases.

Despite the groundbreaking nature of his discovery, Fleming initially faced skepticism and difficulty in obtaining support for his research on penicillin. Many in the scientific community were skeptical of the potential therapeutic benefits of the substance. It wasn't until the early 1940s, during World War II, that penicillin's value became evident. The drug proved immensely effective in treating infected wounds suffered by soldiers, leading to a dramatic increase in its production and distribution.

The introduction of penicillin heralded a new era in medicine - the age of antibiotics. Fleming's work formed the basis for the development of a vast array of antibiotics that have since saved countless lives worldwide. Penicillin was a game-changer in treating bacterial infections and made possible surgical procedures that were previously too risky due to the high likelihood of post-operative infections.

In recognition of his monumental contributions, Sir Alexander Fleming was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945, alongside Ernst Boris Chain and Sir Howard Florey, who played pivotal roles in the large-scale production of penicillin.

Fleming's legacy lives on not only in the countless lives saved by antibiotics but also in his influence on future generations of scientists. His work spurred intense research into the development of new antibiotics and the study of antibiotic resistance, a growing concern in modern medicine.

Comments