The Latest Books About Britain

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

WHAT HOMER’S ODYSSEY IS to epic poetry, Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones is to the comic epic in prose. This time in “On the Bookshelf” we feature the great 18th-century comic novelist’s epic masterpiece— No. 4 on our list of the 10 most British books of all time. Inevitably, Fielding’s eponymous, picaresque hero’s journey takes him to London, where the vices and temptations of the city are held up in contrast to the innocence and virtue of English country life. Indeed, we embellish that theme with a look at the seamy underclass of 18th-century London in Tim Hitchcock’s lively narrative on the subject. Yes, a country boy like Tom would have been overwhelmed by life in the big city of his day. Finally, in this issue we introduce G.W. Bernard’s important new account of the English Reformation. And you thought Henry just wanted to marry Anne Boleyn.

The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, by Henry Fielding. Available in many editions, both soft and hardcover.

“TO INVENT GOOD STORIES, and to tell them well, are possibly very rare talents,” observed Henry Fielding in The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling. Published in 1749, Tom Jones has been hailed as one of the great comic novels of English literature and author Henry Fielding’s masterpiece. Yet novel writing was not Fielding’s first vocation, nor his second. His first successes came as a playwright, and later as a jurist and journalist.

Born at Sharpham Park, Somerset, in 1707, Henry Fielding was a descendant of earls and the grandson of Sir Henry Gould. After an Eton education, Fielding studied law abroad before returning home to work as a playwright. During the years 1728-37, he penned some 25 satirical plays of drama, comedy, farce and burlesque to critical and popular acclaim.

As a young man, Fielding liked the good life, “good wine, good clothes, and good company,” according to another noted satirist of the time, William Makepeace Thackeray. He described Fielding as “tall and stalwart; his face handsome, manly, and noble-looking.” Fielding displayed little self-restraint in his personal life or in his writing. His plays lampooned the government and took aim at the prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole. As a result, the Theatrical Licensing Act of 1737 was enacted, and the subsequent censorship effectively ended Fielding’s career as a playwright.

With his theater career over, Fielding turned to journalism and the law and was called to the bar in 1740. Two years later, he published his first novel, Joseph Andrews, to modest reception. In 1748 he was appointed justice of the peace for Westminster, and a year later he won the same position for Middle-sex. Then came The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, a picaresque novel in which Fielding tackles the subjects of class, marriage for love vs. marriage for money, greed, jealousy, revenge, forgiveness, reconciliation and the search for wisdom. He tells his tale over the course of nearly 900 pages of biting satire. The book went into four editions within its first year, and became a bestseller.

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img2" align="aligncenter" width="627"]

Tom Jones is told in 18 books, each with a narrator who lends cheeky commentary throughout. The narration is so cleverly done it almost seems like a conversation with an old friend. As in the epics of old, the hero finds conflict at home, hits the road and undertakes a journey fraught with pitfalls and adventure. The conflict becomes resolved, and the hero returns home.

This very long and involved tale begins with the master of Paradise Hill, Squire Allworthy, returning home from a journey to find a babe in his bed. He is told that a local girl, Jenny Jones, is the child’s mother, and the kindly and charitable Allworthy sends the disgraced girl away and agrees to raise the child as his own. He names the boy Tom Jones. The good squire’s rather rigid sister Bridget uncharacteristically takes to the child, even after she marries a vile man who is only interested in her inheritance. From this marriage, Bridget has a son named Blifil, a noxious fellow.

The years pass and Tom grows into a handsome and generous young man. He does many kind and selfless acts, without notice or reward, but he is sadly lacking in judgment, and his kindnesses frequently come at the expense of the law. By age 14 Tom “has already been convicted of three robberies…and was universally disliked.” Or rather misunderstood. His thievery was committed to help an impoverished gamekeeper. Also, his interest in the fairer sex leads him into a number of precarious situations.

Meanwhile Sophia, the worthy and delightful daughter of neighboring Squire Western, has fallen in love with Tom. Squire Western wants her to marry Blifil to unite the Allworthy and Western estates, and though Western likes Tom, he has no intention of allowing his daughter to marry a mere foundling. For his part, Blifil wants to marry Sophia for her money and to trump Tom, who by this time has come to the realization that he loves Sophia.

To see these reviews and hundreds more by leading authorities, go to our new book review section at www.thehistorynet.com/reviews

Then Squire Allworthy becomes seriously ill. Allworthy, however, recovers, and Tom gets drunk to celebrate. Blifil lies and tells Allworthy that Tom believed the squire was about to die and was celebrating his impending inheritance. A disappointed Allworthy banishes Tom.

Tom decides to go to sea, and Sophia runs away from home. While on the road Tom meets up with the man everyone, including Allworthy, has come to believe is Tom’s father. As they travel together, they encounter a ruffian attacking a woman of middling years. Tom rescues the woman, a Mrs. Waters, who later seduces Tom at a nearby inn. Further on in the novel, it is revealed that Mrs. Waters is none other than Jenny Jones, and Tom has a very bad Oedipal moment of believing himself to have slept with his mother.

Meanwhile Sophia arrives, learns of Tom’s infidelity and heads to London; Tom discovers her discarded muff at the inn and, realizing that she knows of his affair, follows. There Sophia stays with Lady Bellaston, who becomes intrigued by Sophia’s description of Tom. Upon Tom’s arrival in town, Lady Bellaston arranges a meeting with him, and they begin an affair.

Lady Bellaston keeps up the charade until Tom and Sophia accidentally meet in her drawing room. Sophia and Tom reconcile, but Sophia maintains that she cannot displease her father by marrying Tom. Lady Bellaston, not fond of taking second place, arranges for a friend of hers, who has fallen for Sophia, to rape and then elope with the girl.

Just in the nick of time, as young Sophia is about to be violated, in bursts her father, who has followed them all. Allworthy and Blifil also arrive in London. Meanwhile, Tom gets tossed into prison for assault, and Sophia learns of his affair with Lady Bellaston. Sophia writes Tom and tells him she never wants to see him again, and Tom learns that Mrs. Waters is Jenny Jones, his supposed mother.

It is here that Tom has the epiphany that changes the course of his life. “I am myself the cause of all my misery. All the dreadful mischiefs which have befallen me are the consequences only of my own folly and vice.” Our hero is about as low as low can get, but things are soon to brighten.

While in London, Allworthy learns of Tom’s many acts of generosity and chivalry and uncovers Blifil’s lies. Furthermore, the squire discovers that Blifil had kept from him a letter written by Allworthy’s sister on her deathbed. In it, Bridget confessed that Tom was in reality her son and that she had paid Jenny Jones to take responsibility.

Allworthy banishes Blifil and names Tom as his heir; subsequently Tom is released from jail, Squire Western enthusiastically agrees to marriage between Sophia and the newly elevated Tom, and Sophia forgives Tom. They marry and return to the country, and Western gives them his estate.

And that is making a long story very short.

The comedy in Tom Jones can be low, as when early in the novel Tom retreats into a grove with another girl after daydreaming about Sophia: “Jones probably thought one woman better than none, and Molly as probably imagined two men to be better than one.” Yet it suits the characters and the story, which is incredibly complex, with a huge cast of characters, plot twists too numerous to relate and humor sharp enough to cut a finger.

Allegories run amuck and satire rages. The character names alone—Allworthy, Thwackum, Sophia, the girl’s maid Mrs. Honour—are literary devices. How Fielding kept it all straight boggles the mind. Yet as Thackeray observed: “Fielding, too, has described, though with a greater hand, the characters and scenes which he knew and saw. He had more than ordinary opportunities for becoming acquainted with life. His family and education, first—his fortunes and misfortunes afterward, brought him into the society of every rank and condition of man. He is himself the hero of his books; he is wild Tom Jones….”

ALLYSON PATTON

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img3" align="aligncenter" width="503"]

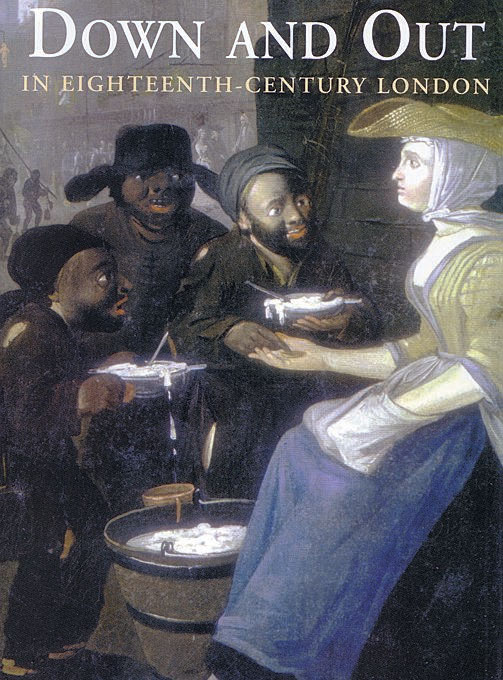

Down and Out in Eighteenth-Century London, by Tim Hitchcock, Hambledon and London, London, 360 pages, hardcover $29.95.

THE GREAT GOOD that Tim Hitchcock does with this intriguing, well-researched, well-written account of the historic poor in London is to tell their story “from below,” in their words and context, and stir debate about who the poor were and what challenges they faced.

Any narrative is part fiction, but all narratives contain some truth, too. One reviewer suggests that though this book is a “sympathetic, lively study,” its author could have relied on a little less fiction and a little more truth.

Yet there is a great deal of truth in Down and Out. The author is careful about the court and workhouse records, memoirs, letters and art he uses. He states that much of the art that depicted begging in the 18th century featured males, whereas most beggars were women and children, often left by their men, who were generally in or killed by military service.

The story of one Sarah Griffin is as brutally sad as any in his history. In 1740, during a period of public begging, she ended up gang-raped and was left to die alone in a barn. Or take this excerpt from a poem by the “Workhouse Poet,” Ann Candler, written in 1802, when she lived at Tattingstone House of Industry: “Within these dreary walls confin’d/A lone recluse, I live,…/No sympathising friend I find,/Unknown is friendship here;/No one to soothe, or calm the mind,/When overwhelm’d with care….”

But there was also much rogue literature that emerged, like a beggar’s ballad, printed in Ned Ward’s History of London Clubs (1709), in this case from a “beggar’s club”: “What tho’ we make the world believe/That we are sick and lame,/Tis now a virtue to deceive,/The Righteous do the same….”

As Hitchcock notes, most beggars also did some work in the “economy of makeshift.” Products were recycled extensively. Among “mobile” jobs were those of sock-seller, mackerel-tout, cinder-shifter, balladeer, linkboy (torch carrier), milkmaid, chimney sweep, prostitute and charwoman. Pennies might be paid for those services and maybe food, drink and a place to stay provided. The disabled, ill and pregnant were seen begging and working. People not settled by parish, and sometimes those who were, spent time in workhouses, way stations for poor people’s many needs.

Begging was sustained by an ambivalent British attitude toward it. Though it was generally illegal to beg, the economy relied on a mobile workforce to perform menial, short-term tasks in cost-effective ways. Supplementary begging was largely tolerated on about 18 holidays yearly, many around Christmastime. Some poor even joined mobs and marauded for money.

Tim Hitchcock is a professor of history at the University of Hertfordshire and co-director of The Proceedings of the Old Bailey (www.oldbaileyonline.org), a Web site containing 100,000 printed trial accounts from 1674 to 1834. The author of Down and Out, which calls to mind the early works of George Orwell, spent 10 years sleeping rough before university work. Like Orwell, he knows of what he writes.

DAVID MARCOU

The King’s Reformation: Henry VIII and the Remaking of the English Church, by G.W. Bernard, Yale University Press, New Haven, 672 pages, hardcover $40.

THE PROTESTANT Reformation that swept across Western Europe in the 1500s was less than monolithic in nature. Reformers in Germany, France, Switzerland and elsewhere, while adhering to many common essentials of faith, each overlaid the reform movement with distinctive nuances that typically led to squabbles among the many resulting reform factions. Nowhere, though, was the reform movement more distinctive than in England, and nowhere was there a reformer as controversial and enigmatic as King Henry VIII.

This new book, which bills itself as “a major reassessment of England’s break with Rome,” explores Henry’s motives, methods and policies during the most dramatic religious transformation in the British Isles since the Dark Age mission of St. Augustine of Canterbury. Bernard shows, convincingly, that Henry’s reformation was the result of a well-formulated, proactive policy, not an inadvertent and shortsighted reaction to his desire to have annulled his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, who had unexpectedly failed to bear him a son. Nor was Henry cleverly manipulated by counselors such as Cromwell, Wolsey and Cranmer, Bernard argues, but instead he played the role of the mastermind who was willing to let his subordinates take the fall when pawns needed to be sacrificed.

The author makes the case for Henry’s disagreement with Rome being sincerely based on religious scruples, not merely a cynical excuse by which he could pave the way for a marital union with Anne Boleyn. “Henry saw himself as God’s lieutenant,” Bernard believes, “whose divinely ordained mission was to purify the church.”

Through an overwhelming mass of documentation, Bernard demonstrates that the king was firmly in control of just such a reform throughout the marriage controversy and its aftermath, and that few of his bishops and courtiers challenged him forcefully, and none effectively.

While Henry responded to this belief in the need for a break with Rome, he stopped well short of taking up the banner of Luther or Zwingli; instead he aimed at a more measured and moderate reform based on his own royal supremacy and his distaste for the “superstition” permeating the Roman church.

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img4" align="aligncenter" width="502"]

According to this view, the dissolution of the monasteries was prompted not by the king’s desire to confiscate the wealth of the church, as so often postulated, but rather to dismantle the infrastructure of the cult of relics and shrines that had flourished at the start of Henry’s reign.

Less controversial, perhaps, is Bernard’s conclusion: “The king’s reformation, for all its radicalism over monasteries and pilgrimage shrines, was not a road towards protestantism. Henry would have no truck with Lutheran notions of justification by faith or Zwinglian doctrines of the eucharist: It is not convincing to present Henry as a protestant, an evangelical or even a half-protestant. But that did not…make him a conservative exponent of traditional religion: ‘catholicism without the pope.’” Indeed, Henry was Henry, a reformer unique unto himself.

BRUCE HEYDT

Briefly Noted:

My Lady Scandalous: The Amazing Life and Outrageous Times of Grace Dalrymple Elliott, Royal Courtesan, by Jo Manning, Simon & Schuster, New York, hardcover $25.

THE EPONYMOUS HEROINE of this putative biography is an inconsequential lady of easy virtue who found lovers and protectors across the upper reaches of Georgian society both in London and Paris.

Wonderfully, the book is far more about her outrageous times, which included the horrors of the French Revolution and the dissipation of the Prince Regent’s court. Ah, some things never change.

A Devon House: The Story of Poltimore, by Jocelyn Hemmings, University of Plymouth Press, Portland, Ore., softcover $19.99.

EVERY GREAT OLD COUNTRY house has its story to tell, and Poltimore’s lovingly told tale could be an archetype. Hemmings traces the evolution of Poltimore House from 16th-century manor to handsome 20th-century mansion. Like so many great countryseats, however, the last century brought hard times. After turns as a girls school, a boys school and a hospital, the house sat empty and decaying for two decades. Now, the Friends of Poltimore have arisen to come to its rescue.

Comments