Spring blooms rape swaddle Hampshire’s North Downs in a golden blanket.Jim Hargan.

[caption id="JourneytoWatershipDown_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

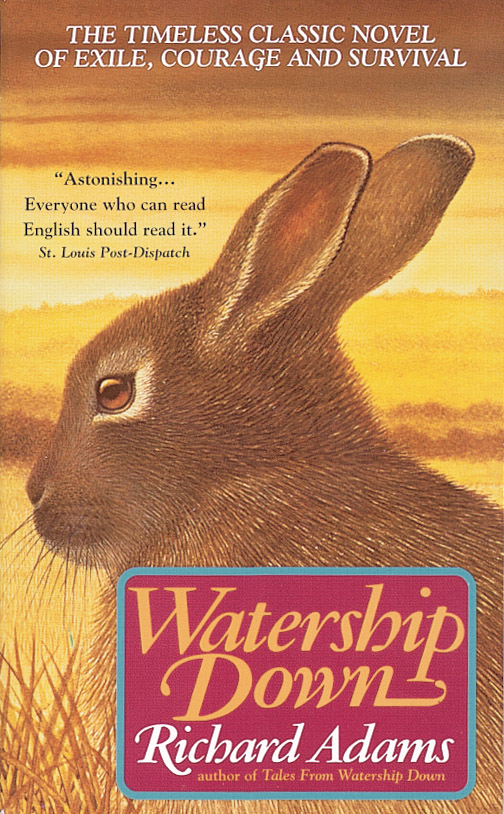

aragtag band sets out across an alien, hostile landscape, pursued by enemies, its individuals’ lives threatened at every moment. They could be hobbits in Middle Earth, or Allied soldiers behind enemy lines in Normandy. But they’re not—these are bunnies. In order to avoid certain death they must hop across seven miles of English countryside, to the remote shelter of a low chalk hill—an epic journey that sweeps across 475 pages of Richard Adams’1972 novel, Watership Down.

[caption id="JourneytoWatershipDown_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

Adams’fable for adults is about a lot of things, and one of them is the English countryside. This is no fictional landscape, idealized and manipulated. Every place in the book is real; Watership Down is a real hill, Nuthanger Farm is a real farm, the footbridges over the River Test are precisely as the rabbits find them. You can visit these places. In fact, it’s a good idea; the rabbits’journey deep into the English countryside reveals some strange and beautiful things.

Adams brings us into a very special landscape from a unique perspective—about six inches off the ground. At this level, you have to stretch up high on your legs to see over the grass. You don’t walk through the grass—you hop, your eyes bouncing from dirt level to grass top and back down. This makes it very difficult to hold a straight line, so you have to stop every once in a while to see where you are. While you can’t see much, however, there are plenty of animals that can see you, particularly when you stand up to look around. Most of them will kill you when they see you; your enemies are The Thousand. Crossing a field becomes an exhausting trek requiring great skill and courage. On the other hand, you won’t have to find a gate—hedgerows are a welcome refuge, not a barrier.

Time, as well as space, is different. Rabbits only live for two or three years. They experience life as an ever-changing sequence that, remarkably, cycles back as the seasons come around. The backdrop to their lives, the English countryside, remains constant and unchanging through a single generation, or even two or three. It may be constant, but it is by no means natural; humans have profoundly altered every square inch of England, and the rabbits must fit themselves into these utterly human landscapes. The rabbits prefer landscapes that are mature, with many species and a wide variety of places to hide, as well as a scarcity of people (prominent among The Thousand). Raw, new landscapes, with people nearby, are deeply hostile.

When we visit this same countryside, we see things very differently. In our decades of experience, the seasons flash past and landscapes change before our eyes. Taxes change, and meadows are plowed up for newly profitable crops. Roads improve, and rich people build weekend estates. The human population becomes larger and wealthier, and deserted ridges become popular picnic sites. In the years since civil servant Richard Adams walked these hills in the 1950s, and chief rabbit Hazel-Rah led his comrades up Watership Down, 16 generations of rabbits have grown and died. Their descendants probably have not noticed this half-century of change, but you will.

The Meadow

In all of Adams’ large and sprawling epic, there is only one fictionalized piece of landscape: the housing subdivision that destroys the rabbits’ original home. The real subdivisions have certainly come close; you can see the goal posts of Newbury’s new rugby field from the site of the rabbits’ warren, on a hillside just south of this bustling West Berkshire town. However, the warren itself remains well-protected by England’s draconian planning laws, prohibiting all new home construction in conservation areas such as this. Homes (and most recently a superstore) crowd up to the edge of the forbidden zone and stop.

Visiting is easy enough and worth the while of anyone who loves beautiful countryside. An old lane, long closed to vehicles but open to walkers, starts across from the former Sandleford Manor—now a boys’ school—and heads east into what was once the manor’s park—now farmland and the site of the bunnies’ original home. After crossing the stile, you can walk through pristine fields and forests seldom seen by outsiders. The land rolls down to the River Enbourne, past a strip of trees and up across fields, to rich, deep forests that hide Newbury and smother its noise. Peas seem to be the thing now; great fields of English peas, covered in their lovely little flowers, line much of the path, yielding their heavy, sweet smell in the spring. When the lane crosses a rivulet, the warren was just up the hill from this spot.

Should you stray from the footpath uphill to where the warren was lodged beneath the fine old copse, you won’t find any rabbits. It’s a hunt club now. Shotgun shells litter the ground, and blinds perch in the great oak trees, like treehouses for grownups. The rabbits are long gone. However, keep your eyes open for deer.

The Commons

When Adams’ rabbits encounter a strange and frightening place, alien to their experience, they are at “Newtown Common—a country of peat, gorse, and silver birch.” They push through thick heather covered in dew, which quickly soaks their fur; they claw over ground made up of soaked peat and sharp, white stones. There is nothing fit to eat and nowhere fit to dig—no food and no cover. Their quest goes on all night, until the bravest are exhausted from fear.

Most marvelously, it’s still there and still a common. That is, Newtown Common remains in shared ownership by the villagers of Newtown, who possess certain rights to use its resources but cannot fence or farm it. In medieval times they would cut firewood and peat, coppice trees for pollards (that is, cut large trees for the poles that would grow from their stumps), graze their goats and sheep in the summer and “mast” their pigs during winter, letting them survive semiwild off the autumn nut and acorn crop.

From our towering viewpoint, easily looking over the inedible heather, it’s a wonderful place. Newtown Common is lush with vegetation of all sorts and flush with wildlife. Beech, oak, pine and birch fight for footholds in the poor soil; underneath, the trees open into large expanses of heather, gorse and tough bog grass. Brilliant yellow gorse flowers succeed to the delicate lavender of heather blooms. A maze of paths crosses over hard, white stones and deep, black peat. Walk softly and watch for a startled grouse or red deer.

[caption id="JourneytoWatershipDown_img3" align="aligncenter" width="504"]

Jim Hargan

[caption id="JourneytoWatershipDown_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

The River Test is groomed as carefully as any cottage garden

The River Test

In its daring raid on the Efrafa warren, the band of rabbits hides out on the far side of a small river, believing correctly that the enemy rabbits would not patrol there. Rabbits do not like wet places, and the River Test is positively soggy. Also rabbits do not like to cross weird human structures such as bridges—something the story’s heroes face with a great deal of trepidation. Most intriguing is the rabbits’escape plan, floating in a punt down the middle of the 30-foot-wide Test, a plan formed by the cleverest of the rabbits, Blackberry.

“On almost any other river, Blackberry’s plan would not have worked,” Adams tells us. But the Test is a special river. First, it’s a chalk river, spring-fed from the water seeping from underneath Watership Down. Its flow is constant and fast, its waters are crystalline and its bed made of sand, gravel and bits of flint. Second, the Test is renowned as one of England’s premier trout fisheries. As such, it is groomed as carefully as any cottage garden, its center kept free of obstructions, its flow carefully managed. When you look at the Test from any of its many bridges, you see straight through the fast, clear water to the few strands of waterweeds waving from the gravel downstream.

Unfortunately the rabbits’exceptional hide-out is now strictly off-limits inside a private estate, Laverstoke House. You can see virtually identical scenery, however, a few hundred yards downstream at Freefolk. Here, a short lane crosses the Test on an arched brick bridge, to dead-end in a hundred yards at the village church. This is a good place to walk the riverbank, enjoying the riot of wildflowers, the clear, cold water and the waterweeds bending in the fast current. The brick bridge is almost exactly like the one upon which the rabbits come a cropper—three arches, each with a scant foot’s clearance at the high point. Downstream is an old concrete weir, still in use to regulate flow. Farther downstream still, public footpaths cross and recross the Test, weaving their way to and from the river, along with fishermen’s paths that line the banks.

Watership Down

From the top of Watership Down, the steep north face of the Hampshire Downs stretches left and right in an endless crescent that reaches to the horizon. Immediately below, the intensely private manor house named Sydmonton Court stands surrounded by its parks and fields, an intact relict of former glories. Most of this long stretch of remote hillside remains exactly as Hazel-Rah and his band first found it.

But not Watership Down.

Not even conservation laws seem to be able to protect countryside once people of wealth and connection covet it. The entire crest of Watership Down, almost two miles in length, has been bulldozed for a horse gallop. Built by a local stud farm to train racehorses, it’s a long, fenced stretch of graveled racetrack, carefully contoured and surrounded by turf. Altogether, it has about as much biodiversity as a parking lot, and no room at all for burrowing animals that might cause a valuable racehorse to stumble and break a leg. It separates the public footpath that follows the crest from the actual edge of the down and from any views. You can go around it at its western end (the easiest approach from the nearest paved road) or cross it on a set of stiles about a half-mile up. Sheep were scarce in Hazel-Rah’s day, an anomaly brought about by low wool and mutton prices throughout most of the 20th century. Lamb prices are high now, and the sheep are back, grazing the steep north face of Watership Down as closely as a golf course.

Enjoy the view, which is spectacular. Then return to the end of the gallop, where a large lump marks the remains of a Bronze Age tomb. The lane that extends southward is the one followed by the bunnies in their raid on Efrafa, its hedges recently replanted. A quarter-mile down this path is a small surviving meadow of downland grass, alive with wildflowers in the spring, crossed by a public path that leads back to the lane. Walk quietly and look closely here and in the hedges that survive across the lane. The rabbits remain, as they always will.

[caption id="JourneytoWatershipDown_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

WHILE VISITING

The Hampshire downlands that include Watership Down sit about 70 miles west of London, occupying a wide, little-visited area between the M3 and the M4.

WATERSHIP DOWN. From the A34 south of Newtown, take the Old Burghclere/Beacon Hill exit, and go east (away from Beacon Hill). In about two miles, the first nondead-end on your right is the narrow lane that climbs Watership Down. When the lane crests out, park and follow the Wayfarer’s Way east a quarter-mile to the crest of Watership Down.

THE RIVER TEST. From Watership Down, continue southward on the narrow lane, past the lovely old farms at Ashley Warren Farm and Hare Warren Farm. Beyond the old Roman Road and Caesar’s Belt, the lane gradually descends to the large riverside village of Whitchurch. Whitchurch is a good place to view the Test; the tiny village of Freefolk, a couple miles eastward and upstream on the B3400, is another.

FOOTPATHS. The Ordnance Survey publishes incredibly detailed maps that show these paths and nearly everything else, down to houses, barns and fences. For the Watership Down area, you will need Pathfinder Maps 144 (Basingstoke) and 158 (Newbury and Hungerford), available from its Web site, www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk.

Comments