Dr. Samuel Johnson, become England’s most important 18th-century men of letters.

"His dictionary offers a delicious banquet of anachronistic words, but because much of 18th-century England stands here revealed, like an encyclopedia of society and thought."

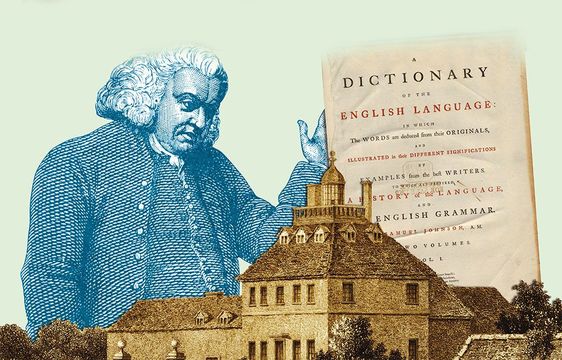

Dr Samuel Johnson, born on 18, September 1709, published his dictionary on 15, April 1755. It is among the most influential dictionaries in the history of the English language.

When I first browsed Dr. Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755), predictably perhaps, I reveled in seeking out the richly descriptive vernacular words of our 18th-century forebears. Bedpresser (heavy, lazy fellow), slubberdegullion (paltry, sorry wretch), fribbler (trifler), belly-timber (food, materials to support the belly), backfriend (a friend backward, an enemy in secret). And I was amazed—and amused—to find how meanings of words have changed. In Johnson’s time, a sneaker was a large drinking vessel, a cruise was a small cup, terrifick meant dreadful, calculus was a stone in the bladder and a jogger moved heavily and dully (still true, perhaps).

The more I delved, the more I was hooked. It is not that his Dictionary offers a delicious banquet of anachronistic words, but because much of 18th-century England stands here revealed, like an encyclopedia of society and thought. Johnson broke the mold in English dictionary writing, focusing on words of everyday usage, as well as “hard words” that earlier glossaries had concentrated on. He was the first to illustrate words with quotations from great writers like Shakespeare, and he set a standard that influenced all later English language dictionaries.

Henry Hitchings in his entertaining Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary (John Murray) refers to “the book that defined the world.” It’s not an exaggeration; Johnson also defined Britain to the world. For 150 years, “the dictionary” meant only Johnson’s Dictionary, so great was its authority before the Oxford English Dictionary (10 volumes, 1884-1928) and before Webster’s had come along in America (1806).

As Hitchings records, even quite recently, when the “first meaning” of terms in the U.S. Constitution have played a part in legal proceedings, it has been to Johnson’s Dictionary, the contemporary arbiter, that American courts have turned: Campbell v. Clinton, February 2000, is just one example. The meaning of declare and war needed to be ascertained in determining the constitutional right of President Bill Clinton to continue airstrikes against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia without explicit authorization by Congress. Johnson’s Dictionary continues to live and breathe.

Samuel Johnson is among Britain’s greatest men of letters, a poet and purveyor of bons mots whose troubled but brilliant character looms larger than life, thanks greatly to his friend James Boswell’s biography. For the 250th anniversary of the publication of his Dictionary, back in 2004, it seemed timely to appreciate what we owe to his magnum opus.

Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary, edited by Jack Lynch (Levenger Press, 2004), offers a great taster, with 3,100-plus selections from the two-volume, 2,300-page original. But to better understand the man and his Dictionary, I followed a Johnson dictum: “Knowledge is of two kinds. We know a subject ourselves, or we know where we can find information upon it.” I headed for Lichfield in Staffordshire, his birthplace and home for most of the first, formative 28 years of his life.

Courtesy of Lichfield City Council

Samuel Johnson was born on September 18, 1709, the first of two sons, to Sarah and Michael Johnson, a bookseller and sheriff of Lichfield. It was a difficult birth, and Samuel was quickly baptized at home—now the Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum on Breadmarket Street—lest he didn’t survive. He grew into a sickly child scarred by scrofula from being fed by a wet nurse whose milk was infected with tuberculosis.

Later in his Dictionary, he illustrated his definition of scrofula with the quotation: “If matter in the milk dispose to coagulation, it produces a scrofula” (from Richard Wiseman’s Seven Chirurgical [Surgical] Treatises, 1676). The condition could be acquired in other ways, but Johnson tellingly related it to his own experience.

“The fact that Johnson was brought up in such a literary environment was key to his development,” says Annette French, museums and heritage officer at the Birthplace Museum.

The reception area of the museum sells books, to give an impression of Michael Johnson’s bookshop, and a tableau in the basement re-creates the family’s kitchen where 9-year-old Samuel famously had an early brush with Shakespeare. “He picked up a copy of Hamlet and became so absorbed in it that when he came to the ghost scene he was suddenly frightened and rushed upstairs to be with people,” French explains. “With books everywhere, he became a very advanced and eclectic reader.” It was a trait that stood him in good stead for his Dictionary, in which he used around 110,000 quotations from luminaries as diverse as Shakespeare, Sir Thomas More, and Sir Isaac Newton, to illustrate the meanings of 42,773 entries.

The Birthplace Museum is bursting with evocative artifacts that tell Johnson’s life story, from a first edition Dictionary and the Dictionary Room to displays of personal possessions. London may have been where he pursued his professional life, but it was Lichfield that made him what he was, and you can catch glimpses of him all around the city. Trace his steps to Dam Street where he learned reading and writing at Dame Oliver’s School, and to St. John Street where he developed a love of classical literature at the Lichfield Grammar School—now replaced by Victorian council chambers. The headmaster’s house of 1682 still stands, and John Lake, a local city guide and member of The Johnson Society, Lichfield, showed me inside. In the study (now the office of the council’s chief executive), he reveals: “It was here that the tyrannical headmaster, John Hunter, beat his pupils into distinction. It’s no surprise that in his Dictionary Johnson defines school as a house of discipline and instruction, with the discipline put first!”

While home life was strained—Michael Johnson was beset by financial worries—Samuel escaped into books and the company of friends. Two men, in particular, helped shape his life: his clever but dissolute cousin Cornelius Ford at Pedmore, Worcestershire, who told him of the exciting world of scholarship and literature in London; and Gilbert Walmesley, a Lichfield Cathedral official living in the Bishop’s Palace in The Close (now the Lichfield Cathedral School), who sharpened his skill as a conversationalist.

For all the discomforts of his childhood, Johnson held Lichfield in lifelong affection, as Lake points out: “He told Boswell it was a city of philosophers whose inhabitants spoke the purest English, and it really was a cultural center. Joseph Addison, Elias Ashmole of Ashmolean Museum fame, and David Garrick were all educated at the Grammar School.” Look in the Dictionary for an explanation of lich, and you find Johnson proudly saluting his native Lichfield with “Salve, magna parens”—“Hail, great parent,” now featured on the city’s crest.

Johnson went to Oxford University in 1728, but lack of funds curtailed his studies, and just over 13 months later he was back in Lichfield working in his dying father’s bookshop. In the following years, he buried his father, dabbled in journalism in Birmingham, married the widow Elizabeth “Tetty” Porter (she was 46 to his 25) and attempted unsuccessfully to establish a school at Edial, three miles west of Lichfield.

Grub Street became synonymous with hack writing. Johnson defined the word: “Originally the name of a street in Moorfields in London, much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries, and temporary poems; whence any mean production is called grubstreet.”

Fortune: “His father dying, he was driven to London to seek his fortune” (Dictionary, Swiftian quotation). In 1737 Johnson set off for London (accompanied, coincidentally, by former Edial pupil and future star actor David Garrick). Johnson was to spend 47 years in the capital, living at 17 or 18 different addresses. After many struggles on the Grub Street of journalism, he did make his reputation as a man of letters and a poet, with triumphs that included his enduring poem “The Vanity of Human Wishes” (1749) and his moral essays for The Rambler periodical (1750-52).

The beginning of his lexicographical endeavors was in 1746 when Johnson agreed to a substantial 1,500 guineas (£1,575) deal with a syndicate of booksellers to write a dictionary. Previous dictionary attempts in English had tended to be glossaries of obscure and technical words rather than day-to-day language, the best exception being Nathan Bailey’s An Universal Etymological English Dictionary of 1721 (it had shortcomings—“cat: a creature well known”).

Yet there was widespread fear that English was degenerating due to uncontrolled change as well as corruption by foreign terms. Academies in France and Italy had marshaled their languages in dictionaries—it was time to standardize and purify English, too.

Lexicographer: “A writer of dictionaries, a harmless drudge….” Johnson proclaimed he could complete the task in three years; he took nine, laboring with the aid of half a dozen assistants in the garret of 17 Gough Square, London, which like his birthplace is now a museum. Throughout, Johnson was distracted by his other writings, motley associates and frequent financial worries, while the death in 1752 of his by now estranged wife plunged him into another of his periodic depressions.

Above all, progress on the Dictionary was slowed by its monumental scale. Johnson devoured previous dictionaries and read voraciously to find quotations to illustrate the words he was to define, marking passages, with a particular word underlined, for his helpers to transcribe onto sheets of paper. He amassed too many quotations and the manuscript was overly messy for the printers to use and had to be redone. After about three years’ labor, he more or less started again.

The trials Johnson suffered are reflected in the Preface to his Dictionary, eventually published April 15, 1755—with his coveted honorary Master of Arts degree from Oxford on the title page. “I have protracted my work till most of those whom I wished to please, have sunk into the grave, and success and miscarriage are empty sounds,” he wrote. “I therefore dismiss it with frigid tranquillity, having little fear or hope from censure or from praise.”

More significantly, his Preface shows a change of emphasis regarding the lexicographer’s role. Prior to commencing work, Johnson had written a plan and sent it to the 4th Earl of Chesterfield, hoping for patronage. In it he had addressed the need for a dictionary to regulate and stabilize language. After nine years of sweat, he now acknowledged the futility of a single authority embalming a language that constantly changed by “general agreement.” His role was more to register than to form it. He also famously fired off a scathing letter to Chesterfield, who had only belatedly warmed to the project in the hope of sharing the limelight. Feel Johnson’s simmering resentment in his Dictionary definition of patron: “One who countenances, supports or protects. Commonly a wretch who supports with insolence, and is paid with flattery.”

The Dictionary, the first standard English dictionary, is a breathtaking achievement for one man. Not the most comprehensive, it nevertheless defined an estimated 80 percent of the words in use at the time. Its focus on “ordinary” words like put and take was meticulous in detail, recognizing that common words in all their subtle nuances were in fact among the most difficult to explain. Take, for example, merits more than 130 numbered meanings, supported by a staggering 363 quotations.

His extensive use of illustrative quotations was Johnson’s greatest innovation in English dictionary writing, making his Dictionary additionally an anthology. He mainly chose authors who “rose in the time of Elizabeth,” revealing his belief that this was a linguistic golden age, with Shakespeare, the best source for the language of “common life,” leading the way. Of course, there were exceptions, including the Bible, Chaucer—and some of his friends.

He also selected quotations on the principle that they should give “pleasure or instruction,” not just illustrate the meaning of a word. His Dictionary nearly morphs into an encyclopedia, with Sir Isaac Newton quoted on prism and refraction, and John Locke on property. The 18th century was a period of rapid development, of the dawning Industrial Revolution and expanding empire. Here is a window on that world: exciting scientific thought (atom, gravity, telescope), new fashions (umbrella), politics (tory, whig) and society (coffeehouse).

At times, Johnson’s own opinions burst through. He censures foreign words that have crept into the language, excelling himself with a double swipe on scelerat, meaning villain, “A word introduced unnecessarily from the French by a Scottish author!” (Despite his famous disparagement of the Scots, most of his literary assistants were, interestingly, Scottish.) At other times, he dismisses words as cant (“corrupt dialect, barbarous jargon”) or suggests obsolete words that deserve to be revived. Occasionally he makes blatant mistakes (pattern:

“The knee of an horse”), and sometimes his etymology is outrageously fanciful. But such weaknesses are exceptions.

The Dictionary met, on the whole, with critical acclaim, though its £4.10s price tag was too high for any the prosperous to afford. It was only when it was serialized and then published in an abridged format that it was widely bought, and dictionaries moved out of the scholar’s library into ordinary people’s homes, including those of English speakers abroad. Nearly every library in the U.S. held a copy and, as noted, the framers of the American Constitution relied on it, forging a piquant Johnsonian link that will continue as long as the Constitution prevails.

Pension: “…in England it is generally understood to mean pay given to a state hireling for treason to his country.” Despite Johnson’s Dictionary definition, in 1762 he accepted a £300 annual state pension from King George III. And he went on to further feats with his eight-volume edition of Shakespeare (1765), his Scottish journeys and the work known as Lives of the Poets (1781).

In 1761 Johnson made his first visit to Lichfield since his 1737 departure, returning several more times before his death in 1784. He once remarked, as an inscription on his statue in Lichfield’s Market Place records, “Every man has a lurking wish to appear considerable in his native place.” He would be pleased to know that his bookshop home prospers and that each September Lichfield celebrates his birthday, including a Johnson Supper of his favorite steak and kidney pudding and apple pie at the Guildhall. He would be rightly proud that with new editions of his Dictionary appearing, another generation of readers is being inspired to a greater love of his and their language—still evolving, still exciting.

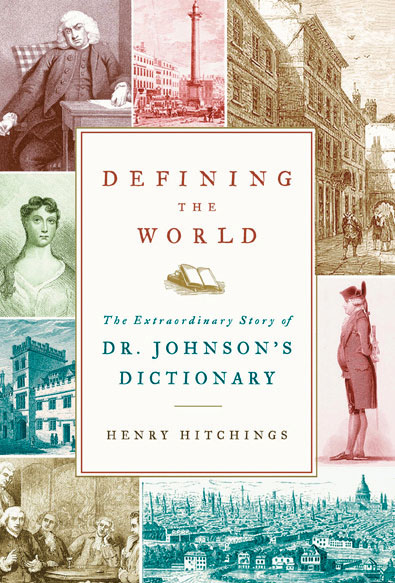

The most important British cultural achievement of the 18th century, according to London writer Henry Hitchings, is Dr. Samuel Johnson’s massive Dictionary of the English Language, which appeared in the spring of 1755. Hitchings’ fascinating book, Defining the World: The Extraordinary Story of Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary, reveals the magnitude of the task and depicts the Dictionary entries as illuminations of Johnson’s brilliant mind. “In more than 42,000 carefully constructed entries, Johnson mapped the contours of the language,” writes Hitchings, “combining huge erudition with a steely wit and remarkable clarity of thought.” While focusing on the creation of the Dictionary, Hitchings also provides a realistic yet affectionate character study of the perennially appealing Doctor.

To assist readers in understanding the centrality of the Dictionary in its author’s life, Hitchings traces the route by which Johnson arrived at the formidable enterprise. Those familiar with Boswell’s classic biography will remember the provincial town of Lichfield in Staffordshire where Johnson was born and raised. Throughout Johnson’s sickly childhood—blindness in one eye, partial deafness, and facial scaring due to a glandular disease known as scrofula—his intellectual interests were fostered by the family bookshop. Reading became a retreat from the wretchedness of what Hitchings aptly describes as “a pinched and narrow world,” and an antidote to the melancholia that would plague him all his life, particularly during the writing of the Dictionary.

A time-consuming but vital part of Johnson’s undertaking, and his most innovative contribution as a lexicographer, was his inclusion of quotations to illustrate the words he defined. His Dictionary contains citations from Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden and Pope, among others. His belief that the difference in meaning in words generally accepted as synonymous must be carefully observed added time to the project. Johnson’s most expressive definitions reveal both his personal experience and his rich imagination.

One emphasis of Hitchings’ book is that while the Dictionary documents the copious vitality of the English language and its literature, it is Johnson’s inimitable spirit—humorous, ethical and perceptive—and warm intelligence that preside over every page. The Dictionary of the English Language defines “lexicographer” as “a writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge that busies himself in tracing the original and detailing the significance of words,” an entry that speaks volumes about Samuel Johnson.

For information about visiting Lichfield and Johnson-themed guided tours, telephone 01543 308209 or visit www.visitlichfield.com.

The Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum is located on Breadmarket Street, Lichfield. Telephone 01543 264972 or visit www.lichfield.gov.uk.

Dr. Johnson’s House is located at 17 Gough Square, London. Telephone 0207 353 3745.

Defining the World: The Extraordinary Story of Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary, by Henry Hitchings, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005, 296 pages, $24.

Comments