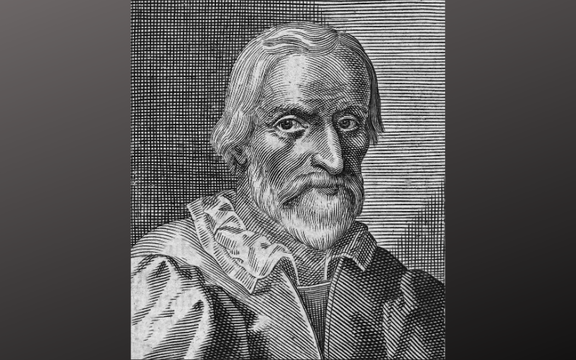

The Venerable Bede.Getty

Venerable Bede was early medieval Europe's greatest scholar and the first to record the history of the English nation. He passed away on May 26, 735 AD.

Along the narrow coastal plain of Northumbria, the River Tyne winds from Newcastle towards the North Sea, lined with oil tanks, heavy equipment, and the relics of the Tyne's industrial importance. The scene is not picturesque. It's hard to imagine that just over the crest of the riverbank lie the rural remnants of one of Europe's most historic centres of learning, the ancient Saxon monastery of St. Paul's, Jarrow.

About 1,300 years ago, however, under the reign of Northumbria's sagacious King Aldfrith, this sparsely populated northern monarchy enjoyed a golden age. Jarrow's most famous resident and the most important figure of this generation of art and learning was a humble monk named Bede. The Venerable Bede was early medieval Europe's greatest scholar and the first to record the history of the English nation. His reputation alone made this one of the most important historical and religious sites in Europe.

King Ecgrith of Northumbria gave the land at Jarrow to the church in 681. Benedict Biscop, a Northumbrian nobleman, accepted the gift and sent an abbot named Ceolfrith along with 10 monks and 12 novices from St. Peter's monastery at Wearmouth, 12 miles away, to found the new monastery of St. Paul's.

The 12-year-old Bede was present at the consecration of the new church on 23rd April 685. 'I was born on the lands of the monastery, he later wrote, and on reaching seven years of age, I was entrusted by my family first to the reverend Abbot Benedict and later to Abbot Ceolfrith for my education. I have spent all the remainder of my life in this monastery and devoted myself entirely to the study of Scriptures.

In truth, the humble monk's studies encompassed a wide range of disciplines, including astronomy, classical languages, medicine, and seemingly everything else his imagination and resources would allow. Certainly, Bede's intellectual range went much further than the Bible itself. While many of his 60 works are biblical commentaries, he also wrote on natural history, science, poetry, and history. It is, in fact, for his monumental Ecclesiastical History of the English People that Bede is best remembered.

The routine of the abbey day seems designed to deaden rather than awaken intellectual curiosity. Celebrating the offices of the canonical day itself was an arduous, time-consuming, and endless cycle. After the first office, sung at 2 am, any rest came in snatches before a general predawn rise to private prayer and manual duty. Daily life was ordered, shoe-horned in between the constant rhythm of the services from prime to lauds. In the midst of this ascetic and repetitive life, however, Bede wrote a prodigious canon of scholarship by any historical standard. It is impossible to appreciate the scope of Bede's effort without recalling the conditions under which he wrote, working with hand-sharpened tools on coarse surfaces, minimal artificial light, and communication no faster than a horse on uneven ground. Services of worship that marked his priestly vocation regularly interrupted his attention, and for months at a time, the Northumbrian climate was damp, chilly, and dark. Pen and paper, light and warmth would have been to Bede luxuries beyond imagination.

Exactly how Bede came to be called Venerable remains obscured by the passage of time. The popular account suggests that a monk, inscribing in stone upon his tomb, chiseled Here in this grave lie Bede's bones and left the job incomplete when he quit for the day. The next morning, he discovered that an angel had added the word Venerable. Whatever its origin, the epithet has been regularly coupled with his name.

While many of Bede's works have become relics of intellectual history, of course, his Ecclesiastical History of the English People remains singularly important. Beginning with Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain, Bede's narrative spans almost 800 years of history, encompassing political, military, and social life as well as the coming of Christianity and the rise of the early church. His account is a primary source of information on such events as the martyrdom of St. Alban, the coming of the Saxons, St. Augustine's arrival in Canterbury, and the Synod of Whitby.

The Venerable Bede never travelled farther than the city of York. He never met a Pope or world leader. He never saw a library better than his own. Bede died in his cell at Jarrow in 735, at the age of 63. He was buried in the church, but in the 11th century, a cleric from Durham stole his bones and placed them with those of St. Cuthbert. His remains now rest in the Galilee Chapel at Durham Cathedral.

Within a hundred years of Bede's death, his book was known all over Europe. The Ecclesiastical History formed the basis of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, compiled in the late 9th century, and popularized the BC/AD dating system, the now-common measure of time based on the birth of Christ.

The monastery itself did not fare as well. In 794, Viking raiders pillaged the coastal monasteries of Northumbria. Fire destroyed the Saxon buildings, and by the middle of the 9th century, the Jarrow community was abandoned. Bede's legacy was not forgotten, however, and inspired the foundation's rebirth in 1074. Its historic importance may have made it one of the first monasteries suppressed at the Reformation, and since 1536 St. Paul's has been a parish church.

The remains of the monastery's domestic buildings, dating mostly from the 11th century, still surround the church. The original Saxon basilica serves as the chancel of the present parish church. Its 7th-century foundations are still visible in the main aisle. Much of its dressed stone came from abandoned Roman buildings, perhaps even Hadrian's Wall. One of three splayed windows contains Saxon glass made in monastic workshops, the oldest glass in Western Europe. An ancient chair in the chancel, presumed to have been the master's chair from the medieval cell, has long been known as Bede's Chair.

English Heritage has recognized the importance of both the site and the work of Bede. Just a few hundred yards across the neat park, they have created Bede's World. The modern complex seems an unlikely departure for English Heritage, but then again, little of Bede's original world remains visible, and there is nothing to conserve.

The new interpretive centre, with its paved courtyard and atrium, offers exhibitions and displays of Bede's life, the monastery at Jarrow, and early Northumbrian history. Bede's World also incorporates a late-Georgian manor, Jarrow Hall, now a restaurant and temporary exhibition site, as well as an herb garden laid out in a traditional monastic plan.

Along the banks of the Tyne, English Heritage is developing Gyrwe, an Anglo-Saxon farm recreated to demonstrate life outside the 8th-century monastery. Replica buildings, rare animal breeds, and ancient grain and vegetable crops are all part of the maturing farmstead.

If Bede might recognize the Gyrwe farm, he certainly would recognize nothing else of modern Jarrow. The industrial age turned the sleepy village into a suburban morass of roundabouts and housing estates. Getting there requires threading through Gateshead and the Newcastle southern suburbs, or jumping off the A19 just south of the Tyne Tunnel.

In the midst of this modern confusion, though, a visit to St. Paul's, Jarrow, and Bede's World is a worthwhile exercise. It's quiet here -- an oasis in the desert din of modern life. One can almost imagine the studious monk labouring away over his manuscript under the light of grey Northumbrian skies.

* Originally published in June 2006.

Comments