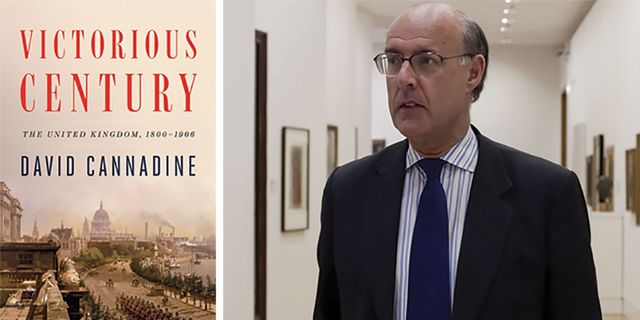

David Cannadine Photo Credit: Tom Miller

The author chats with BHT about embracing complexity, the function of history and the responsibilities of historians.

When asked about his favorite Victorian lives, David Cannadine starts off with a politician. “Well, of course Gladstone, how could he not be? The greatest 19th-century British Prime Minister. And the Queen herself, an utterly extraordinary figure.” From there, he shifts to writers: “Carlyle and Tennyson, along with Dickens and George Eliot.” Then, a couple of wild cards: “Florence Nightingale, a remarkable figure given that it was a man's world, yet she made it a long way. And, at the beginning of the century, The Duke of Wellington. He fought in so many battles and was never hit once, nor was his horse, Copenhagen.” It's unsurprising he can namecheck the stallion Wellington rode into Waterloo. If he wanted, Cannadine could probably give the beast its own biography.

Called “the preeminent public historian of his generation” by The Guardian, Cannadine is the president of the British Academy, has held positions at Princeton, Cambridge and Columbia and has written 17 books—including his most recent, Victorious Century.

He's also the Deputy Chairman of Historic Royal Palaces and has chaired the National Portrait Gallery trustees in London; he's given more public lectures and is a fellow at more societies and academies than one can reasonably list. “There are many various ways of being an historian,” says Cannadine, who appears to be trying all of them. “I believe history has a public function and historians, if they have the opportunities, should and can undertake public service.”

It takes a while to get those titles out of him. He mentions others, but only as an aside, while explaining the institutional history behind his works: “Now, Victorious Century is a volume in a series called The Penguin History of Britain—of which I am the general editor—which was meant to supersede the old Pelican History of England, which came out during the early and mid-1950s and was showing its age by the nineties, as these things do…” He emphasizes that title change, from England to Britain, “perhaps reflecting a growing awareness of the fact that Scotland, Ireland and Wales may need some attention as well.” Always teaching, he's quick to reference the work of other historians, such as G.M. Trevelyan, Eric Hobsbawm and contemporaries like Richard Evans. (He brings up G.M. Young twice within 20 minutes.)

When asked about his position as the editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography series, he again pivots. “One of the things that's worth mentioning is that the Dictionary of National Biography, which is the predecessor of the ODNB, was, of course, very much a Victorian enterprise, created during the 1880s and 1890s, edited in the first instance by Leslie Stephen, who was a quintessential Victorian man of letters…..” As Cannadine delves into those beginnings, he sheds some light on the Victorian historical perspective. “They believed Carlyle's phrase, that the history of the world was really the history of great men and women—and the 19th century was certainly awash with many important figures—but history is, of course, much more than that.”

Beggars and Peasants assembled for Indian meal, July 1847 depicts the Irish Potato Famine. - DOWD FAMILYHISTORY

For that reason, Victorious Century tracks and mixes many different types of history—of people, events, expansions; of scientific, financial, political and cultural changes. “One of the challenges in writing any general survey is to get the balance right—and to try to connect [it all],” says the author. “The driver to the book, in a way, is politics…but I also wanted to try to do full justice to the processes: industrialization, urbanization, imperialism, and so on, as fully as I could.”

The period itself creates a kind of partisan split. Some view the era as a time of prosperity, global range, technological breakthroughs and unrivaled world power—even the birthplace of modernity. “A time, as it were, that we should try to get back to,” Cannadine says. ‘The alternative view, of course, is that the 19th century was racist, classist, sexist, misogynist—almost all of the vices regularly held up to opprobrium today seem to have their origins there.” Cannadine takes special note of a certain growing sense of anxiety during the second half of the century—a feeling that British dominance was, perhaps, a bit of a fluke: “That it probably wouldn't last, and it didn't.”

As the epigraph of the book says, It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. “For most people, probably, it came pretty much in between,” Cannadine adds. Though Dickens wrote those lines about the previous century, it applies well to his own era. The point, Cannadine explains, is to “get beyond these simple binaries to try to understand this rich, varied and, in some ways paradoxical and contradictory civilization.” I wonder if he's ever considered the easy, comfortable path of a reductive interpretation—until I recall he's answered that already, while addressing the role of historians.

“It's often the predilection of pundits and politicians and policymakers to say that the world is very simple. It seems to me that it's actually the job of historians to say, no, the world is very complicated and you ignore those complexities at your peril, and at ours. To that extent, I think the historian's job is to say that nuanced complexities are very important elements in understanding how the world is.”

Victorious Century: The United Kingdom, 1800-1906 (Viking) goes on sale February 20.

Another Day, Another Dollar

WIKIPEDIA

Another job: Cannadine is one of three external experts on the Banknote Advisory committee, which helps select the faces on UK money. Next up: J.M.W. Turner, whose £20 notes, featuring his 1799 self-portrait, will be in billfolds in 2020. “It was enormous fun,” he says, explaining how focus groups whittle down public suggestions. “Before this committee, it was simply a decision on the part of the Governor. I think there was a feeling that the procedure ought to be perhaps slightly more consultative.”

Growing Old in the Victorian Era:

“Life expectancy was much, much lower than it is today. Most people died before they were 40, or during their 40s. This is a world without anesthetics, antibiotics or antiseptics. Most of the figures that we know about— Wellington, Tennyson, Carlyle, Victoria, Gladstone—are all living about twice the age of most people,” Cannadine says.

"It's as if Donald Trump was 150 rather than 70--and that's a thought that boggles the mind a bit. In that sense, it was a very strange world where most of the people in power were, by the standards of the time, extraordinary old. Some of it was luck and good genes. But, of course, also, to some degree, the higher up the social scale you were, the longer your life expectancy was likely to be--which is still true to this day. Long life improved your chances of becoming a major historical figure."

Comments