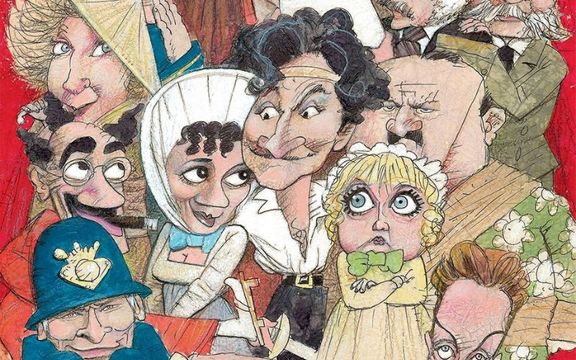

Sir William Gilbert, William Conrad, Tim Curry, Angela Lansbury, Kevin Kline, Linda Ronstadt, Dana Huntley, Groucho Marx, Beverly Sills, Joel Grey, Eric Idle, Sir Arthur Sullivan.

From Barataria to Titipu, the rollicking, madcap light operas of Gilbert & Sullivan parodied Victorian England and still delight audiences around the world.

Today the operas of Gilbert and Sullivan seem as timeless as Shakespeare and scones. Yet when they opened, these musical frolics were topical as well as charming, like rhyming episodes of The Simpsons. They gamboled through the subjects of the day, laughing at the latest crazes and poking fun at pillars of the British empire.

Read more

In 1875, when William Schwenck Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan began to collaborate in earnest, they were already important men. Gilbert was a successful playwright, theater critic and humorist; Sullivan was a sought-after conductor and the most famous composer in England. Luckily, Richard D’Oyly Carte recognized that these singular talents could also work together to realize his dream of creating English comic operas.

The London theater manager was looking for a third item to form a triple bill. Gilbert showed him the script for the one-act Trial by Jury, and Carte enthusiastically suggested that he ask Sullivan to collaborate on it. The two had worked together several years earlier on a hastily produced operetta called Thespis, or The Gods Grown Old, most of the music for which has been lost. Although its run was respectable, this piece about a troupe of actors who meet the Olympian gods in their dotage was an artistic disappointment, and probably only Carte saw a future in the duo.

When Gilbert and Sullivan started on Trial by Jury, however, the stage was set for success. Carte gave them the rehearsal time they had lacked with Thespis. Gilbert now knew he must demand better-set design, costumes, acting, and production. And perhaps most important, the British audience had changed.

Yum Yum, Pitti Sing and Peep Bo are little maids from school in The Mikado, most popular of the Gilbert and Sullivan canon. ARENAPAL/TOPHAM/THE IMAGE WORKS

As incomes rose during the Victorian era, theater audiences grew in size and sophistication. Raucous pantomimes, breathtaking spectacles, melodramas, and translations of racy French plays were still popular. But educated audiences were also beginning to enjoy parodies of classical subjects, such as Greek mythology and the plays of Shakespeare, and they attended opéra bouffes that lampooned popular operas. These audiences would soon appreciate the wit and cultured allusions in Gilbert and Sullivan’s operas.

Theater craft was changing as well, moving gingerly toward verisimilitude. Some reformers argued that actors should not declaim their parts, but speak more naturally, and that plays should be written for ensembles of actors, not as flimsy showcases for a star. As a librettist and director, Gilbert was influenced by both these ideas.

In Trial by Jury, which opened in 1875, there were no prima donnas, and the chorus played a prominent role, as it would in subsequent operas. The lyrics were witty and pointed, for Gilbert wrote about a subject he knew. As a young man, he had worked—quite unsuccessfully—as a barrister. His libretto about a woman who sues her former fiancé for breach of promise, only to become engaged to the opportunistic judge who hears the case, pokes fun at both saccharine ideals of love and the dignity of the bar.

In composing for the piece, Sullivan developed techniques he would use for the next 20 years. His music never overwhelms Gilbert’s words, and it assists their quicksilver swings in meter and mood. Adding another layer of humor to the opera, he refers liberally to the music of Verdi, Donizetti and Bellini to make musical comments on the characters.

Although Trial by Jury was a success, Gilbert and Sullivan did not collaborate again until 1877. By then Carte had raised the funds necessary to take over the Opéra-Comique Theatre. There he established his first opera company.

There were no prima donnas, and the chorus played a prominent role.

As frequently happened, the prolific Gilbert recycled a previously published work for the plot of the company’s first production, The Sorcerer, in which a magician gives the inhabitants of a village a love potion. His delighted audiences understood that this “dealer in magic and spells / In blessings and curses / And ever-filled purses” referred to a family in Lancashire making a fortune in the patent medicine trade.

In the cast were many of the performers who would go on to play leads in the company, notably George Grossmith and Rutland Barrington. (Jessie Bond joined for the next opera.) With them, Gilbert began to develop some types he would use in subsequent collaborations. As director, he asserted that his works must “be played with the most perfect earnestness and gravity” to increase their comic effect.

In the next opera, H.M.S. Pinafore, or The Lass That Loved a Sailor, Grossmith played Sir Joseph Porter. The character was based on W.H. Smith, who had risen, on the strength of his book and newspaper outlets (still operating today) to become First Lord of the Admiralty, though he too had never been to sea.

Gilbert’s libretto both questions and upholds the Victorian class system. The daughter of the Pinafore’s captain loves one of the ship’s sailors. But their social disparity prevents them from marrying until, in the kind of quick reversal that Gilbert so enjoyed, the sailor hears he was switched at birth and is really the captain of the ship!

H.M.S. Pinafore was a rousing success, not only in London, where it opened in May 1878, but throughout America, where unauthorized—and often unrecognizable—versions of it were playing to packed houses. Carte decided that the next opera, The Pirates of Penzance, or The Slave of Duty, would open in New York, under Gilbert and Sullivan’s direction, so American audiences could see an accurate production. On December 31, 1879, it opened at the Fifth Avenue Theater in New York City.

Like Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance features its own pompous commander singing a patter song, and it, too, pokes fun at the class system. At the end of the opera, the pirates are saved from jail and each receives a bride because:

They are no members of the common throng;

They are all noblemen who have gone wrong.No Englishman unmoved that statement hears,

Because, with all our faults, we love our House of Peers.

Perhaps the real subject of the opera, however, is earnest Victorian morality and sentimentality. The hero, Frederic, is led into a series of ridiculous situations by his punctilious interpretation of duty. After being mistakenly apprenticed to a pirate when his father had wanted him bound to a pilot, Frederic joyfully renounces the pirate band on his 21st birthday, vowing to fight it as a soldier, until he learns he was born on February 29 and thus must serve it for another 61 years!

The pirates, however, feel themselves similarly constrained. Being orphans, they refuse to harm other orphans, no matter how rich or powerful, and, not surprisingly, everyone they capture claims to be parentless. All ends happily, however, when their identities are discovered, and each pirate is united with a sweet young girl.

In 1881, the pair’s next opera, Patience, or Bunthorne’s Bride, opened. It spoofs some well-known adherents of the Aesthetic Movement: artists such as Oscar Wilde, Algernon Charles Swinburne and James Whistler, who believed in “art for art’s sake” and the languid search for beauty as the aim of life. The opera’s two leading men are a composite of the three artists. One of them, Bunthorne, is described as:

A pallid and thin young man,

A haggard and lank young man,

A greenery-yallery, Grosvenor Gallery,

Foot-in-the-grave young man!

Wilde, who had seen the opera on opening night, praised Grossmith, who played Bunthorne, as even more “amazing” than himself.

Patience was such a hit at the Opéra-Comique Theatre that Carte finally felt safe to construct a custom-made theater for his company. He built the Savoy Theatre close to where John of Gaunt’s Savoy Palace had stood during the Wars of the Roses. Elegant and modern, it was the first public building to be lit entirely by electricity. On October 10, 1881, Patience moved to the new stage at the Savoy.

Their next production, Iolanthe, or The Peer and the Peri, opened at the Savoy in 1882. This frothy concoction of fairies and the House of Peers appealed to an age enamored of supernatural tales. But the opera also had its topical elements. Everyone recognized the Lord Chancellor as William Gladstone, the Queen of the Fairies as Victoria and Private Willis as her beloved gillie John Brown.

The critics loved Iolanthe, but some were uneasy with Sullivan’s growing career in light opera, which they claimed was diverting him from more serious and lasting work. Today, many maintain that Sullivan worked best when collaborating with Gilbert and drawing on the styles of other composers. Sometimes he parodied them, but more often he looked to the idioms of other composers for inspiration, turning to Rossini for his patter songs, Schubert for modulation and Mendelssohn for a liquid, melodic line. And like many contemporary composers, he drew on folk songs, particularly Irish tunes, English ballads and sea shanties.

‘Because, with all our faults, we love our House of Peers.’

Although Sullivan’s score for the next opera, Princes Ida, or Castle Adamant, was among his best, the work as a whole drew mixed reviews in 1884. Audiences were probably dismayed by its theme of war between the sexes. They may also have found its jokes about female higher education and evolution (almost every male character is depicted as a “Darwin man, though well-behaved / At best only a monkey shaved”) a bit too intellectual.

Sullivan was also dissatisfied. When the time came to start another opera, he declared, “It is impossible for me to do another piece of the character already written by Gilbert.” The composer was tired of contrived plots and of bending his music to the needs of tongue-in-cheek libretti. Like the critics, he believed he was wasting his talents on comedic opera.

Noel Harrison performs as Major General Stanley in the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players production of The Pirates of Penzance. LEE SNIDER/PHOTO IMAGES/CORBIS

For weeks their partnership seemed over—until Gilbert luckily hit upon the theme of The Mikado, or The Town of Titipu to lure Sullivan back. The story goes that a Japanese sword falling from Gilbert’s library wall gave him the idea, but he had only to look about him to see that the Japanese already fascinated the English. Indeed, a highly popular exhibition of Japanese culture was currently on view in Knightsbridge.

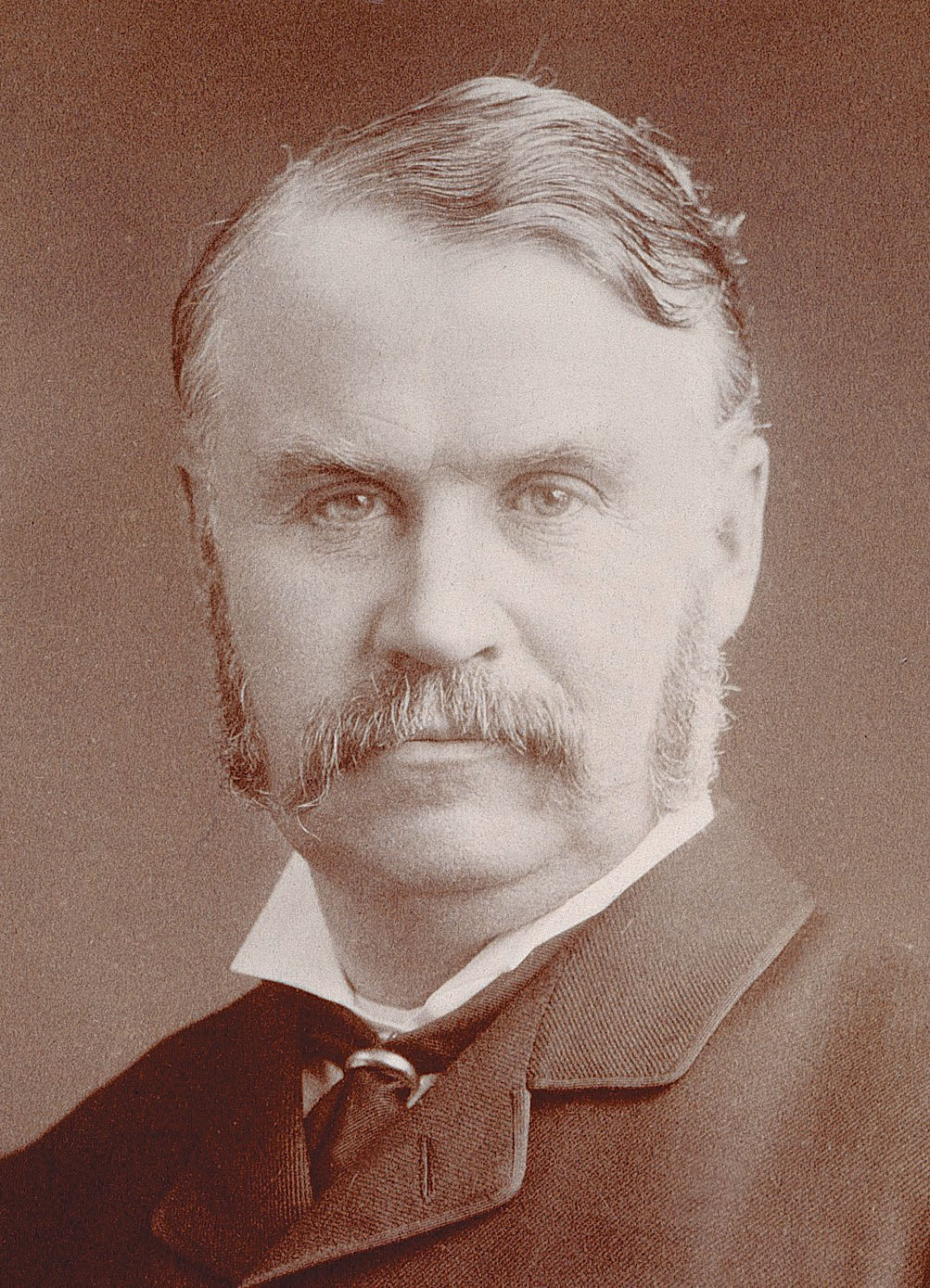

Sir William Gilbert (1836-1911) . THE GRANGER COLLECTION, NY

Just as Gilbert had insisted that the costumes and sets of Pinafore accurately represent the Royal Navy, he now procured robes that were genuine or exact replicas of Japanese garments, and he engaged a geisha to teach the female singers appropriate deportment. Soon Japanese fashions were the rage from London to San Francisco, as Mikado mania swept the world following its March 14, 1885, opening at the Savoy. The opera ran for 672 consecutive performances in London and is still the most popular of Gilbert and Sullivan’s works.

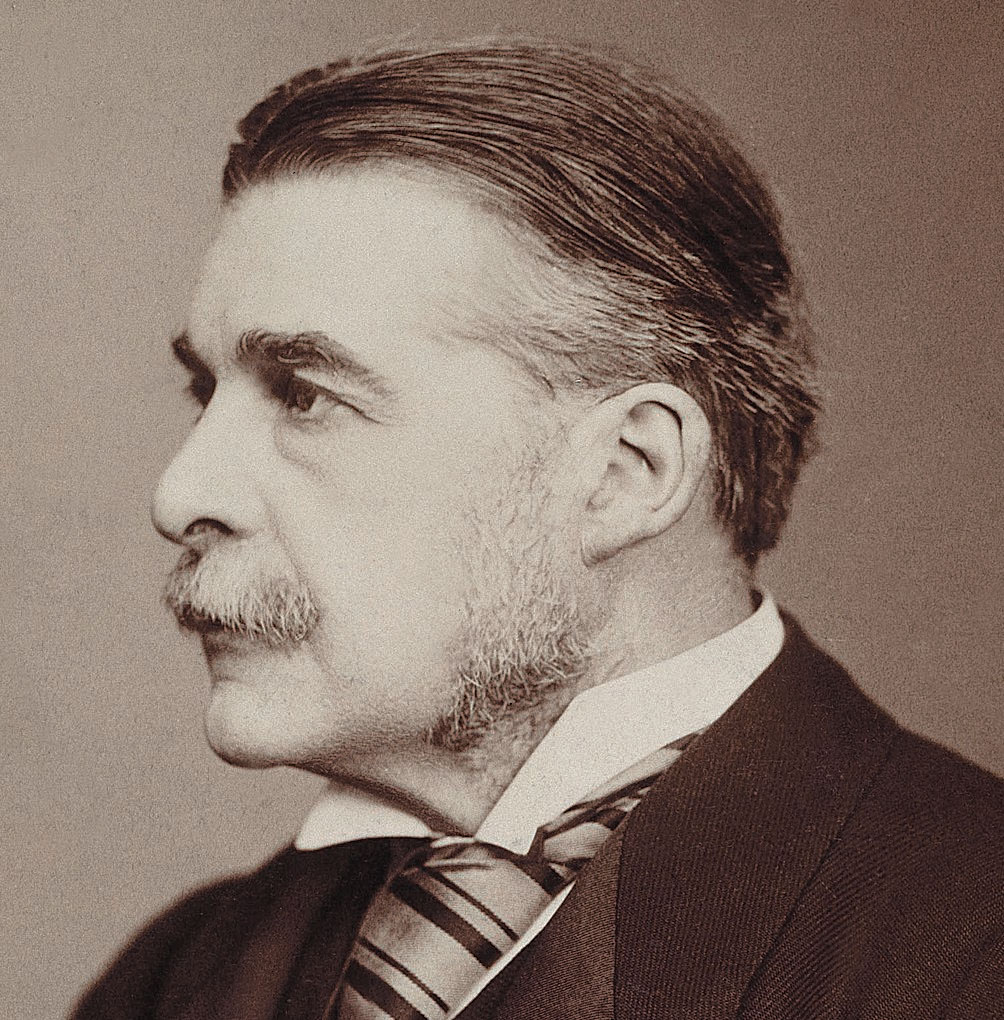

Sir Arthur Sullivan (1846-1900) . THE GRANGER COLLECTION, NY

With Ruddigore, or The Witch’s Curse, however, the pair’s difficulties returned. Although Sullivan had approved the story, as he usually did before Gilbert wrote a libretto, Ruddigore still had too much of the supernatural to please him. A spoof of melodramas, it features ghosts, a dastardly villain, a mad woman, stalwart men and a heroine who lives life according to her etiquette book—hardly the emotionally rounded characters that Sullivan longed for. In addition, the reviewers were now openly accusing Sullivan of squandering his genius.

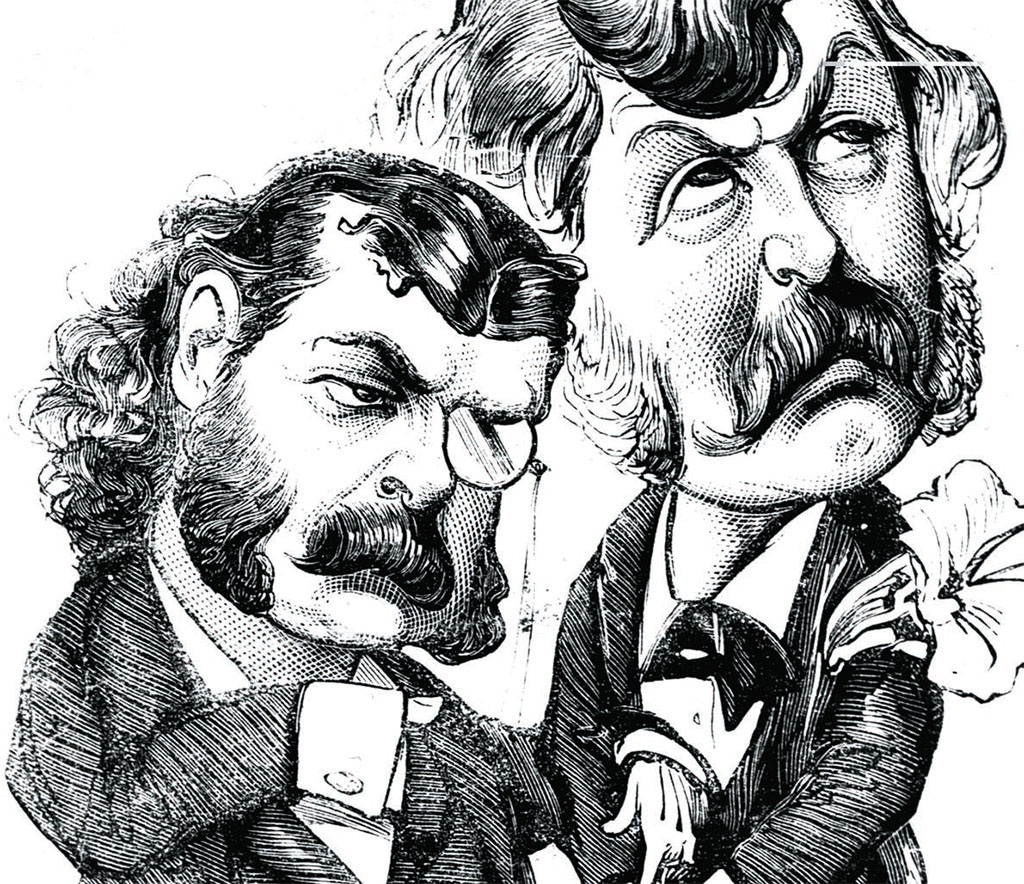

Tthe theatrical pair are caricatured as Aesthetes in the production of Patience in 1881. LEE SNIDER/PHOTO IMAGES/CORBIS

Doubtless, he would have ended the partnership, if he had not needed its proceeds to live opulently among the rich and titled.

Some reviewers also complained that Gilbert’s plots and comic devices were becoming repetitive. He was stung. In Princess Ida, he had self-confidently parodied himself as the critical King Gama, who sings:

Each little fault of temper and each social defect

In my erring fellow-creatures I endeavor to correct.

To all their little weaknesses I open people’s eyes;

And little plans to snub the self-sufficient I devise;

I love my fellow-creatures–I do all the good I can–

Yet everybody says I’m such a disagreeable man!

And I can’t think why!

In the next opera, The Yeomen of the Guard, or The Merryman and His Maid, the exasperated Gilbert now speaks through a jester who complains of the difficulty of satisfying his employer (i.e., the audience):

Then if you refrain, he is at you again,

For he likes to get value for money;

He’ll ask then and there, with an insolent stare,

“If you know that you’re paid to be funny?”

Despite his comedic obligation, Gilbert did give Sullivan well-rounded characters in The Yeomen. Perhaps not coincidentally, this is Gilbert’s only Savoy opera without a satiric target. Audiences applauded his tale of wrongful imprisonment, blindfolded marriage and love lost as well as found in Tudor times, but critics compared Gilbert’s libretto unfavorably to Sullivan’s music. Gilbert felt increasingly unappreciated.

Linda Rondstadt and Rex Smith star as Mabel and Frederic in the 1983 movie adaptation of The Pirates of Penzance. UNIVERSAL/THE KOBEL COLLECTION

In 1889 Gilbert and Sullivan’s last great opera debuted: The Gondoliers, or The King of Barataria. With sparkle and verve, it mocks social leveling and republicanism—a growing threat to the British crown in those days of socialist agitators. The opera also features some of Gilbert’s oft-used plot devices, cowardly policemen and switched babies, but neither Sullivan nor the critics seemed to notice.

In recent years, strains within the D’Oyly Carte Company had been growing. Several leading actors had left in search of higher salaries. Gilbert felt snubbed by the critics. A kind but irascible man (and a despotic director), he had frequently quarreled with Sullivan and Carte. They, however, were always on good terms with each other, which probably made him feel left out.

The tensions between Gilbert and his partners exploded during the run of The Gondoliers. Going over the books one day, Gilbert was appalled at the sum spent to mount the opera (£4,500) and angry that it included new carpets for the front of the house. He claimed that Carte, as the owner of the Savoy, should absorb that cost; Carte argued that carpets were an operating expense that the three partners should pay jointly. Letters, scenes, even a highly public lawsuit ensued. Gilbert and Sullivan did not work together for several years.

They rejoined for Utopia Limited, or The Flowers of Progress, which debuted in 1893. Although the opera received good reviews, this story of an idyllic South Seas island that emulates England did not catch on with the public, and it closed after a merely respectable 245 performances. Three years later, The Grand Duke, or The Statutory Duel ran only half as long.

An era was over. After decades of ill health, Sullivan died in late 1900; Carte followed him a few months later. Gilbert lived on for another 10 years, writing, as he always had, a variety of works for the stage.

Wit and high spirits—’the very model’ of English comic opera.

In a low moment, Gilbert predicted, “Posterity will know as little of me as I shall know of posterity.” During the early 20th century, this prophecy seemed accurate, for the public was losing its taste for his works. Then in 1919, Carte’s son Rupert, taking an enormous chance, brought 10 of the Savoy operas with new costumes and sets back to London’s West End. The response was electric. Tours and more seasons followed, and in 1929 he moved his company into the newly renovated Savoy. Although Carte’s company folded in 1982 and reformed in 1988 only to suspend performances in 2003, the works of Gilbert and Sullivan have been, since Rupert’s day, in continuous production throughout Britain and the world.

The Savoy Theatre on London’s Strand was purpose-built for the D’Oyly Carte Company in 1881. KIM MYUNG JUNG KIM/PA/EMPICS

These operas have been staged in nearly every country and are particularly popular in America, where countless regional companies are dedicated to their performance. Their topicality may be largely forgotten, but their wit and high spirits live on, making them “the very model” of English comic opera.

* Originally published in May 2016.

Comments